“At two in the afternoon, I’m home in bed. I have three heating pads plugged in; one for my stomach, one for my lower back and hips, and one for my mid back, where the pain often just sits. My body is literally wrapped in heat, and still … the pain makes it difficult to focus.” (1)

Daily fatigue. Intermittent nausea without specific food triggers. Constipation, then diarrhea. Deep, stabbing pain with intercourse. And knowing that every month you will end up in bed, curled into a ball, pounding ibuprofen for three days. Every day I hear patients who have been living with undiagnosed or untreated endometriosis describe symptoms like these.

Many of my patients have had debilitating periods since they were teenagers and were told their symptoms were normal—that they just had “bad periods.” In fact, studies have shown that 70% of teenagers with severe menstrual pain ultimately are diagnosed with endometriosis. (2) In many cases, birth control pills can make their symptoms manageable until their 20s, when they stop taking birth control in order to try to get pregnant, or the pills simply lose effectiveness in alleviating symptoms.

Remarkably, endometriosis is actually as prevalent as asthma, affecting an estimated 6-10% of women. (3,4) And the real-life impacts of the condition are highly significant: Women affected by the disease lose an average of 11 hours of productivity per week, and the estimated burden on society is $119 billion per year, based upon lost wages, lost productivity and medical costs. (5) So why does everyone know about asthma, but not endometriosis?

A DIFFICULT DIAGNOSIS

Endometriosis is most commonly described as the presence of endometrium, which normally lines the uterine cavity, outside of the uterus. However, endometriosis actually would be better described as mutated endometrium, given that its biochemical makeup and hormone receptor profile is much different from those of normal endometrium. It is best thought of as an estrogen-dependent chronic inflammatory disease that often starts with dysmenorrhea but can later progress to persistent pain affecting more than just the female reproductive organs. It can mimic interstitial cystitis/painful bladder syndrome, irritable bowel syndrome, and pelvic floor muscular spasm and myalgia. Since women are often told their symptoms are “normal” in their teens and then develop such a wide variety of symptoms from other organs, it’s no wonder the average patient in the United States suffers for 7-12 years before getting a diagnosis. (5)

Part of the diagnostic challenge is that endometriosis is often not visible on ultrasound, CT or MRI, and isn’t detectable by any reliable blood work. As a result, patients are often sent on a round-robin of evaluations by various specialists. Unfortunately, by the time of diagnosis, endometriosis often will have transformed from a disease once limited to painful menses, into a chronic pain condition affecting multiple body systems.

MEDICAL MANAGEMENT

Guidelines have been developed by various consortia on the treatment of endometriosis, but controversy and uncertainty remain over best practices. Medical management, rather than surgery, has been the recommended first-line therapy for many years. And while it is commonly taught that close to 75% of patients with dysmenorrhea — including endometriosis — will have relief from pain with a birth control pill, a closer review of the literature finds little quality evidence to support this. (6)

Injectable GnRH agonists (e.g., leuprolide acetate and danazol) have been reserved for recalcitrant symptoms due to a greater risk of more serious side effects. These agents are now mostly being replaced by a growing number of GnRH antagonists (e.g., elagolix/Orilissa) that can be taken orally and have better side effect profiles. These medications, however, have drawbacks. Their duration of use is limited due to the long-term effects of estrogen suppression on bone mineral density. Moreover, no medication — from combined birth control pills to GnRH antagonists — has been shown to destroy or eliminate endometriosis or improve pregnancy rates. (7) Some endometriosis is simply resistant to medical treatments, due to progesterone resistance and aromatization of testosterone to estrogen by endometriosis lesions themselves. (8)

THE LapEX APPROACH

For those patients who fail medical therapy, there is evidence to support surgical treatment of endometriosis, a method that is endorsed by major gynecologic societies across the world. Surgical treatment has been shown to decrease pain compared with diagnostic laparoscopy, and to improve spontaneous pregnancy rates in infertile patients with endometriosis. (8,9) The LapEX (laparoscopic excision of endometriosis) approach is a minimally invasive technique centered on the concept that endometriosis, like cancer, should be removed as fully as possible at time of surgery to decrease the risk of recurrence.

Until recently, the majority of endometriosis surgeries attempted to destroy endometriosis lesions by means of surface ablation/fulguration, rather than by complete removal. Published rates of recurrence with this technique, which are as high as 60-80% at two years, have been attributed to so-called “invisible endometriosis” that could not be seen, or to development of new endometriosis. Many experts, however, argue that there is no such thing as invisible endometriosis (10) and believe the high recurrence rates are due to inadequate surgical treatment and lack of recognition of more subtle peritoneal changes. Atypical peritoneum not classified as classic endometriosis lesions has been shown to have endometriosis in as many as 50% of specimens. (11) Additionally, recurrence on repeat surgery is most commonly found at the same sites as initial treatment or on the border of initial treatment sites, suggesting incomplete initial treatment. (12) Long-term follow-up on patients who have undergone excision surgery with uterine and ovarian preservation have lower reoperation rates (20-50%) at five years, with even lower rates of pathologic confirmed endometriosis on reoperation. (13)

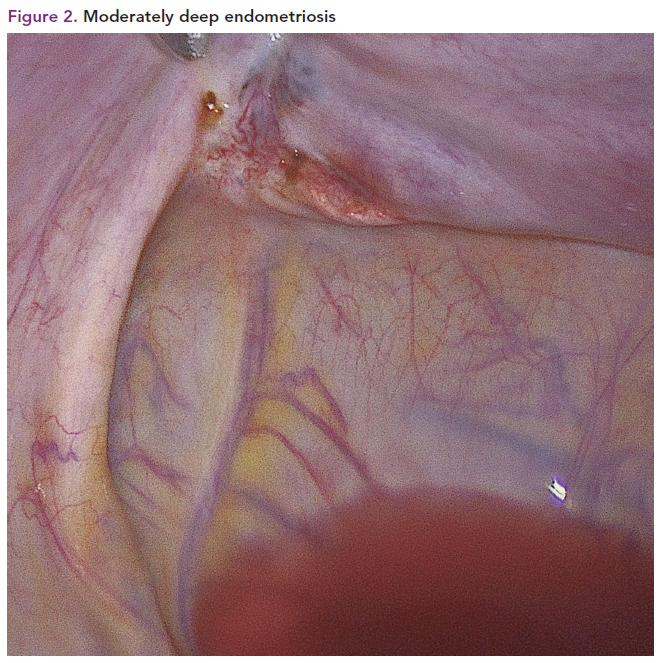

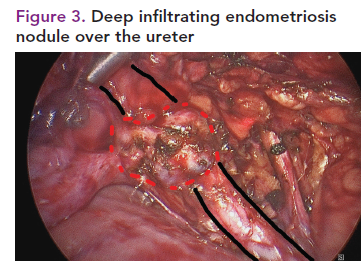

Treatment of endometriosis by excision also provides pathological evidence of the disease and allows the surgeon to remove disease over vital structures such as blood vessels, the ureters and the bowel. It also allows the surgeon to assess whether a lesion is superficial (Figure 1), moderately deep (Figure 2) or deeply infiltrating (Figure 3), so technique can be adjusted to decrease the chance of leaving disease behind.

Why isn’t all endometriosis treated with excision? Compared to other techniques, excision is more difficult, takes longer and carries more risk of surgical complication due to the more aggressive approach. For these reasons, patients may only be offered ablation/fulguration or complete hysterectomy and castration (removal of ovaries) to eliminate the source of estrogen that stimulates the disease. While total hysterectomy and castration are effective, I would argue that they are often not necessary, and carry the long-term risks associated with early menopause: osteoporosis, heart disease, shorter lifespan, and risk of venous thromboembolism and breast cancer with hormone replacement therapy. (14)

In trained, skilled hands, organ-preserving surgery with excision of the disease — rather than the removal of the uterus and ovaries — can alleviate pain and suffering for many years. I prefer to use a free-beam carbon dioxide laser for tissue cutting because it allows for precise control of cutting depth with no thermal spread to damage adjacent tissue. This allows the laser to cut tissue right over structures such as the ureter, blood vessels and intestine, which cannot be done as safely with other energy sources.

MULTIDISCIPLINARY CARE AT SENTARA MARTHA JEFFERSON HOSPITAL

When lesions invade more deeply, they can involve other pelvic organs such as the intestine, ureters or bladder, and these patients may require more extensive surgery to remove the disease and eliminate the source of pain. Studies of a condition called deep infiltrating endometriosis (Figure 3) show long-lasting improvement in pain and organ dysfunction with excision techniques, which can include segmental resection or shaving disease from the involved organs. Recurrence rates for bowel excision of endometriosis range from 0-9% at 5 years. (15)

Surgical management of these challenging cases of endometriosis is very much a team effort. In addition to the surgeon, operating with a carbon dioxide laser requires a laser technician, a skilled surgical assistant, a top-notch surgical tech and a knowledgeable circulating room nurse. Additionally, this type of complex surgery often requires a multidisciplinary surgical team. Sentara colorectal surgeon Zachary Gregg, MD, is often involved in cases where bowel involvement is suspected preoperatively. Endometriosis in the thoracic cavity — on the lung, diaphragm or pleura — is present in about 1% of endometriosis patients. In these cases, Sentara thoracic surgeon Christopher Willms, MD, collaborates for combined laparoscopy and video-assisted thoracoscopy (VATS) exploration.

THE FUTURE

Research continues to focus on finding better noninvasive testing methods that can detect disease without surgery. Candidates include serum testing of a combination of serum markers (CA125, endocan, YKL-40 and copeptin) and measurement of circulating micro-RNA sequences. (16) The promise of earlier diagnostic certainty could allow for earlier referral to endometriosis centers of expertise before unnecessary or incomplete surgery is performed. Perhaps the most important achievement in recent years, however, has been patient-driven advocacy, which has led to increased awareness through social media and school nurse education programs by organizations such as EndoWhat? (www.endowhat.org) and EndoFound (www.endofound.org).

CONCLUSIONS

Endometriosis, an estrogen-dependent chronic inflammatory disease that is difficult to diagnose without laparoscopy, can cause infertility, painful intercourse and menses, and multiorgan chronic pain and dysfunction. Medical therapy is often successful in suppressing symptoms, but a fair number of patients require surgery. Laparoscopic excision of endometriosis is the optimal surgical method of treatment.

This article was originally posted in

Sentara Martha Jefferson Magazine.

REFERENCES

1. Campbell, Leah. (March 3, 2020) What it’s like living with endometriosis. Accessed Oct 21, 2020.

https://www.leahcampbellwrites.com/2020/03/03/what-its-like-living-with-endometriosis

2. Janssen E, Rijkers A, Hoppenbrouwers K, Meuleman C et al. Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: A systematic review. Human Reproduction Update 2013; 19:570-582.

3. CDC.gov. (2020). CDC - Asthma. [online] Available at:

https://www.cdc.gov/asthma/default.htm [Accessed Oct 21, 2020].

4. Giudice, L. C. Clinical practice. Endometriosis. N. Engl. J. Med. 362, 2389–2398 (2010).

5. Nnoaham KE, Hummelshoj L, Webster P, d’Hooghe T et al. World Endometriosis Research Foundation Global Study of Women’s Health consortium. Impact of endometriosis on quality of life and work productivity: a multicenter study across ten countries. Fertil Steril. 2011 Aug;96(2):366-373.e8.

6. Vercellini P, Cortesi I, Crosignani PG. Progestins for symptomatic endometriosis: a critical analysis of the evidence. Fertil Steril 1997;68:393–401.

7. Hughes E, Brown J, Collins JJ, Farquhar C et al. Ovulation suppression for endometriosis for women with subfertility. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007:CD000155.

8. Practice bulletin no. 114: management of endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Jul;116(1):223-36.

9. Dunselman GA, Vermeulen N, Becker C, Calhaz-Jorge et al. European Society of Human Reproduction and Embryology. ESHRE guideline: management of women with endometriosis. Hum Reprod. 2014 Mar;29(3):400-12.

10. Redwine DB. ‘Invisible’ microscopic endometriosis: a review. Gynecol Obstet Invest. 2003;55(2):63-7.

11. Albee RB Jr., Sinervo K, Fisher D. Laparoscopic excision of lesions suggestive of endometriosis or otherwise atypical in appearance: relationship between visual findings and final histologic diagnosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2008;15(1):32–37.

12. Taylor E, Williams C. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: location and patterns of disease at reoperation. Fertil Steril. 2010 Jan;93(1):57-61.

13. Shakiba K, Bena JF, McGill KM, Minger J et al. Surgical treatment of endometriosis: a 7-year follow-up on the requirement for further surgery. Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun;111(6):1285-92. Erratum in: Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Sep;112(3):710.

14. Rodriguez M, Shoupe D. Surgical Menopause. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2015 Sep;44(3):531-42.

15. Roman H, Tuech JJ, Huet E, Bridoux V et al. Excision versus colorectal resection in deep endometriosis infiltrating the rectum: 5-year follow-up of patients enrolled in a randomized controlled trial. Hum Reprod. 2019 Dec.

16. Ahn SH, Singh V, Tayade C. Biomarkers in endometriosis: challenges and opportunities. Fertil Steril. 2017 Mar;107(3):523-532.